In my previous blog Coming to Grips I, I described the proper methods of gripping and securing the Italian weapon to the wrist. Today I wish to address my concern with binding the weapon to the wrist. This concern is not in its use but with the incorrect or misuse of this aid to the hand. From here on the binding device will be referred to as the “wrist-strap”.

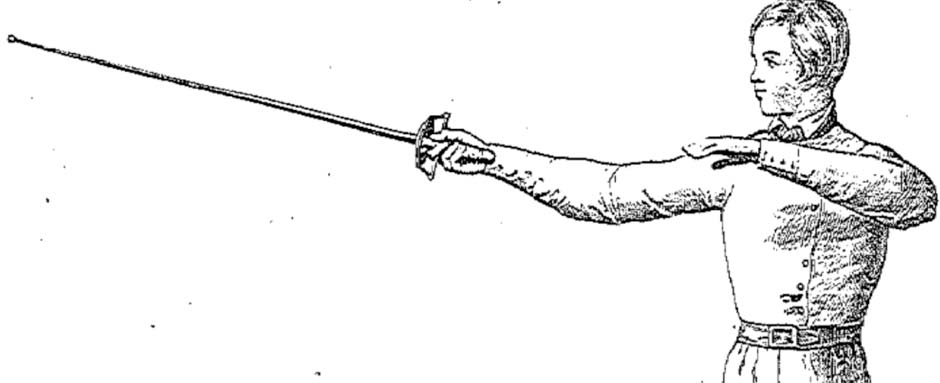

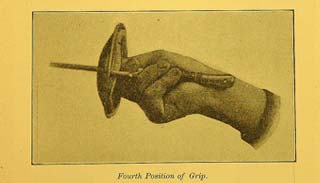

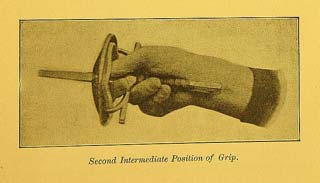

In classical Italian fencing treatises and manuals one finds very precise instructions along with illustrations and/or photographs of the proper method of gripping the Italian foil. (Figure 1 & 2.) However, it is interesting that while the authors describe the wrist-strap, few of these texts actually show the securing of the Italian weapon to the wrist via some sort of binding. In nearly all of the ones that I have read the hand is depicted with all of the fingers properly placed upon the ricasso, crossbar and grip.

During my nearly forty years of experience I have observed many fencers utilizing the Italian foil resorting to what I call the “pinch-method” of manipulating the foil meaning that blade movement depends entirely upon the pinching and releasing of the ricasso with the index finger and thumb.

This leaves the securing of the weapon to the hand entirely reliant on the wrist-strap. This incorrect method results in the practice of fencers taping their fingers and/or crossbar with adhesive tape to prevent blistering of the fingers. For that matter even without the use of the wrist-strap blistering should not be an issue as tactile sense should have been developed when learning to properly finger the cross-bar, ricasso and grip. Thus, what many fencers utilizing the Italian foil in fact practice is at odds with what is specified by Italian masters.

I have observed fencers with their fingers jammed in the guard as deep as possible with only the ring finger resting upon the grip while the pinky is barely if at all upon it. (Figures 3 & 4.) I have also seen the wrist-strap worn excessively tight thus immobilizing the wrist and in some cases cutting off blood circulation to the hand.

These extreme methods usually fatigue the hand and wrist very quickly and lead the actions of the weapon to be executed from the elbow and shoulder. These methods are contraindicated in the use of the Italian weapon as I have already explicated in my previous blog. Burton must have made similar observations as he says that,“the rigidity of the grasp reduces the movements to a few rigid extensions and contractions“.

The observations and commentaries on the method of utilizing the wrist strap made by those who have never been trained in Italian fencing only serve to continue the erroneous assertions of the how the Italian weapon is manipulated. Additionally, those fencers who do not adhere to the correct use of wrist strap also carry a major part of the responsibility for these misconceptions.

The responsibility of dispelling the misapprehension about Italian fencing and the usage of the wrist strap must fall directly on the shoulders of those who profess to be practicing the classical school(s) of Italian fencing. Adherence to Italian theory and technique is a must.

Unfortunately there have been the incessant polemics among the varied school(s) of Italian fencing. The nonsense has always been centered on which is the “pure” Italian school. Furthermore, the rivalry that existed for generations between the Italian and French schools of fencing exacerbated the situation. Exponents of each school never tired of espousing on the merits and superiority of their particular school and the inferiority of the other. In my view it is presumptuous to make any kind of assessments as to the technique of any school of fencing without having trained in the particular school.

It is even a more sad state of affairs when inherited biases are passed on from one generation of masters to the next. This must cease! We who are fencers and masters living in what is supposed to be an age of instant communication and where information is easily accessed should be more open-minded. We should fully realize that no one has a monopoly on the ownership of fencing and the truth. At the end of the day, it is never about any particular school of fencing rather it is about the ability of the individual.